But, let me first give you a small intro on both.

In .NET, when you build a web application, what you typically do, is use ASP .NET (either webforms or MVC) and host your application in IIS. This framework has been around for quite some time, and it has really become big. For some applications, this model can be bloated, since it runs a lot of things you don't really need in your application.

What they wanted to aim for at Microsoft with OWIN and Katana, is build a basis for a framework, that is really light weight, with just the essential things for a web application in it. And if you need extra's you just pull them in as you need them. More or less similar to what you would do to a nodejs server application. Very light weight, but also very powerful.

Along came OWIN, which is a specification for how you can build a web server that can host .NET code. It sits between a hosting environment, which in this case can be either IIS or something else, like a Windows Service, or a simple Console Application, and your actual application code. Any additional middleware, like authentication, can use the OWIN abstraction to be plugged into your application.

So, what does OWIN actually define or specify? Well, the most important part of the OWIN specification is the application delegate, which looks like this:

using AppFunc = Func<

IDictionary, // Environment

Task>; // Done

The application delegate has an argument of type IDictionary

The second argument of the application delegate, the actual return type, is a Task, that will be returned once it has finished processing. You will see the usage of this Task once I start building up some more practical examples. What you will notice, with this task, is that the OWIN architecture is asynchronous by design.

The application delegate is a way of hooking into an OWIN server. Meaning that if you want to hook into an OWIN environment, you will need to have a method that complies to the signature of this application delegate.

Now, where OWIN is a specification, Katana is Microsoft's implementation of this specification. In Katana you can find a couple of OWIN hosts either for IIS, or for self-hosting. You will also find a couple of classes that help you with talking to OWIN, so you don't need to, for instance, take values directly from the environment dictionary. And you will also be able to find a couple of middleware components, like authentication, ...

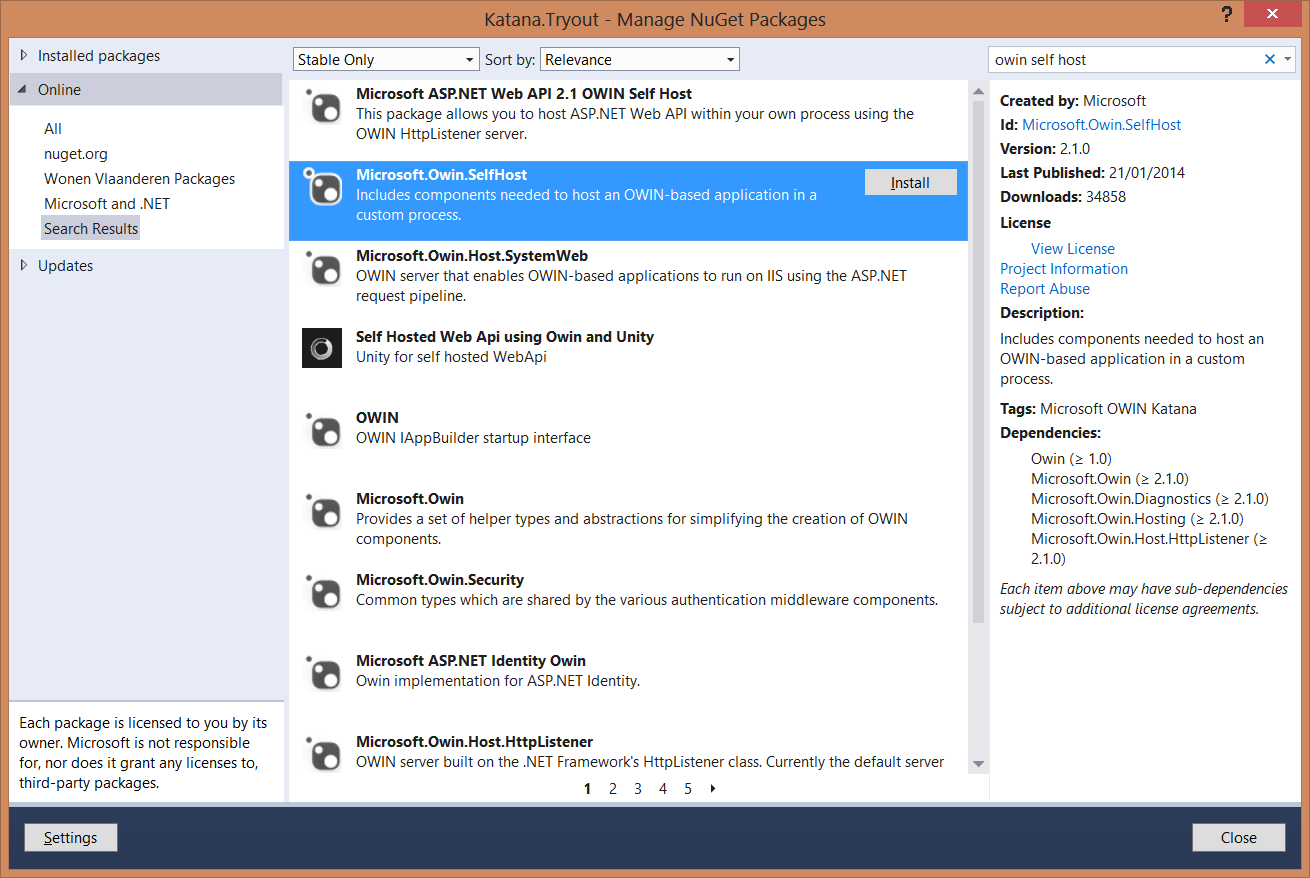

So, let's build a small application with Katana. For this we start of with an empty console application, which we will use as a host for our application. In this we will install the OWIN self host nuget package.

Once we have this, we can start hosting an application. For this we use the WebApp class which represents the self hosting OWIN server and tell it which url it should listen on. We also give it a configuration.

The configuration class is based on convention, it needs a Configuration method that takes an IAppBuilder as an argument.

Now we can start configuring our OWIN host. First thing we will do is a very simple host, which prints out some information of the response that came in, and which returns a string that says Hello OWIN and Katana. For this we use the Run method on the IAppBuilder. This will get a context, which gives us access to the environment variable.

As you can see in the code example, the interface is async by default. The Request and Response properties give us easy access to the data in the environment variable.

When we run this example, we can go to the localhost:4321 uri. It will give us the following response:

And in our Console, we can see the method and URI printed out:

So, that's a really simple example. We can also add some preprocessing or postprocessing to our request. For this you utilize app.Use. This will take 2 arguments, the context, but also a reference to the next middleware delegate in the chain. Whatever you want to do as preprocessing you put before your call to the next delegate. Whatever you want as postprocessing, you put after the call to the next delegate.

This gives us the following output:

Another way of programming this, is with separate classes instead off with delegates. The same example than looks like this:

You create a class with an Invoke method. This method will get the environment dictionary directly. If you want to use the OwinContext instead, you can new it up. Your next delegate this time will not be passed as an argument to the Invoke function, but will be passed as a constructor argument.

With all this you can already do some nice stuff. Beware though, since the API will still be subject to changes. For people wanting to try this on non Windows machines, there's also a Nowin nuget package, that also runs on Mono. Hope this entises you to try some of this stuff out.